Extraterrestrial life

Article curated by Holly Godwin

We've taken revolutionary steps in space exploration, and now scientists and non-scientists alike are asking questions about distant solar systems and galaxies. Questions like... are there any other habitable planets? How many of them have atmospheres? And, most of all... is there extraterrestrial life?...Are we, or are we not, alone?

Biomarkers for alien life

Scientists keep a look out for ‘biomarkers’ when searching for alien life. Biomarkers are the characteristics of the Earth’s atmosphere that, when present on other planets, indicate the possibility of life. These include the presence of molecular oxygen, water, carbon dioxide and methane.

Learn more about Biomarkers on Exoplanets.

In the search for biomarkers, cosmochemists are exploring the chemical composition of other worlds – from interplanetary dust particles to samples returned from space missions. Asteroids with similar violent chemical pasts to our planet or high carbon contents are particularly promising as these might have developed similar atmospheres and oceans to Earth.

Water on other planets

For life as we know it to be viable, water is a necessity. Humans are composed of 60% water and cannot survive without it for more than a few days. Some species need less, and are less dependent on water, but we don't yet know of any that don't need it at all. However, this does not necessarily mean that life is dependent on water universally. It's possible that other life forms may have evolved with alternative biochemistries, reliant on other elements altogether.

Learn more about dependency of life on water.

2

2

However, some doubts have been raised about the validity of Goldilocks Zones, as surface water is thought to have been detected on celestial bodies outside a zone, most commonly by cosmochemists via absorption spectroscopy – a method of analysing the light from a body to determine what the body is made of. The water present on these planets might be maintained by processes such as tidal heating and radioactive decay, or pressurised by other means. It's also thought to be possible for water to be present on rogue planets or their moons[1]. Because these planets are migrating through cold outer space, any water present is assumed to be frozen a lot of the time, and thus inaccessible for life (but we don't know).

So while these zones may be a good place to start the search for extraterrestrial life, maybe we should not limit ourselves to searching solely within their scope.

Learn more about Circumstellar habitable zones.

MarsScientists looking for water on Mars have used ground-based telescopes and detected polar ice caps; the Mars Express satellite and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have been able to estimate how much of these is frozen water (the majority of the rest being frozen carbon dioxide). Elsewhere, the Mars Global Surveyor has made measurements of the amount of water in the Martian atmosphere, and measurements of rock and soil samples strongly suggest the presence of water in the ground at some point in the past, as do a number of geological features observed from satellites. Other water may be trapped deep in permafrost (permanently frozen soil), or much deeper underground in large frozen reservoirs[2] – none of these are very accessible for living things.

3

3Is there life on Mars? Probably not, though with ice present, it remains a possibility. If there is, it's likely in the form of microbes rather than anything more advanced. Perhaps a better question though, is was there ever life on Mars? Since we now believe there was once liquid water on the surface, this is a strong but unproven possibility, and is driving several Mars missions from Curiosity (NASA) to ExoMars (ESA).

2

2

Ganymede Ganymede, Jupiters largest moon, may actually be composed of several layers of salty waters and ices – much like a club sandwich. Because of the huge pressures thought to exist on Ganymede's ocean floor, scientists had previously believed that the layer next to it's rocky core would most likely be ice. This was a problem for the idea that primitive life may have formed on Ganymede at some point in it's history. Rock/liquid water interfaces important for the potential development of life – many scientists believe that life on Earth most likely began at hydrothermal vents on our own ocean floor. The new findings from this study of Ganymede imply that instead of the core being next to water – because of the high salinity, denser fluid water would sink toward the core in Ganymeade allowing water and rocks to interact. By using computerised simulations and models, scienitists have concluded that a likely composition of Ganymede's ocean is water sandwiched between up to three ice layers, with a salty liquid water layer next to the socky sea floor.

3

3Europa The thickness of the ice covering the surface of Europa is still an unknown. Europa is thought to have either a thick layer of ice with areas where liquid water has reached the surface or a thin layer of ice with liquid water underneath. Water flows up through the cracks in the surface caused by asteroid impacts and gives the surface a very young appearance. Scientists have agreed that these large cracks along with evidence of movement of large areas of terrain and the water smoothing out the surface all suggest that there is a sheet of ice with liquid water underneath. Temperatures on Europa’s surface range between 53K and 111K – far too cold for liquid water! – but a volcanic inner layer or tidal heating due to Jupiter's gravitational effects mean that some of it melts. But how much? We don't yet know!

2

2Exoplanets

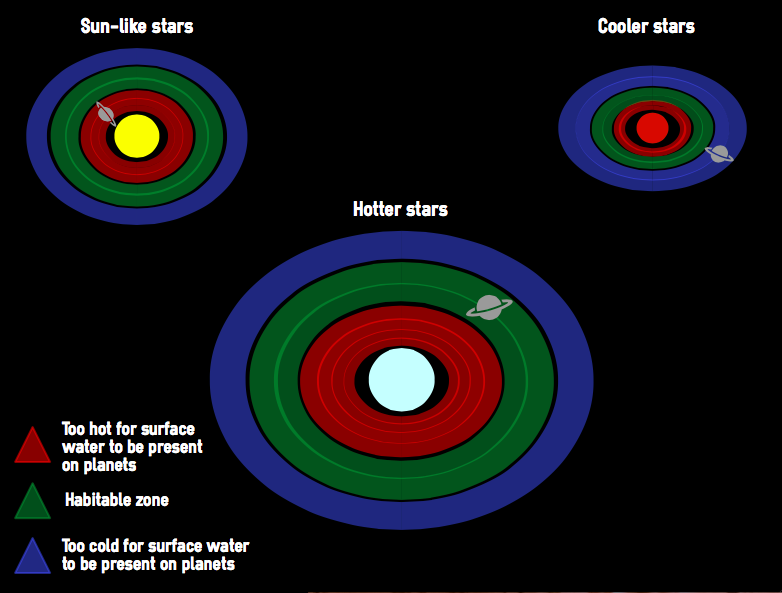

Scientists have been discovering planets outside of our own solar system since 1988, and the rate at which these have been found has increased exponentially across these years. The nature of planets is varied, and the possibility of any of them supporting life depends upon several factors, including the elemental makeup (detected by cosmochemists) of their stars, which affects how fast they burn and so how long they live and where the habitable zone lies. It also affects the atmosphere and geology of its planets, and so whether they can support life.

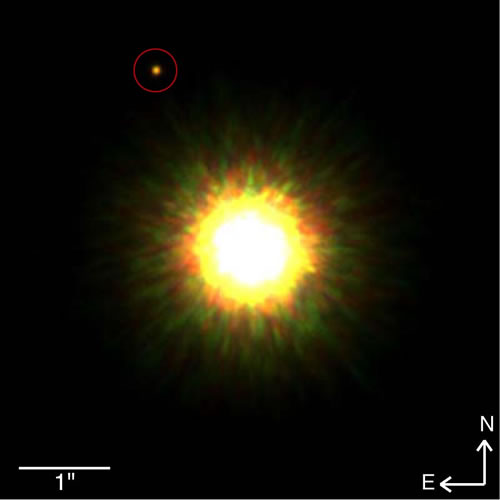

Detecting biomarkers on distant exoplanets is hard because they're closer to their own star than Earth. This means the light we observe from these planets is often masked completely by the radiation emitted from their star, making analysis far more complex. Even when a planet is directly observable, an extremely high resolution telescope is required to distinguish between the light from the planet and the light from the star. To a lesser extent, radiation from other distant objects can also make it harder to distinguish what radiation belongs to the planet: even our own atmosphere can interfere and confuse results!

Learn more about direct imaging of exoplanets.

2

2

Methane on other planets

Mars

Methane has been detected in the Martian atmosphere both by Earth-based telescopes and by the European Mars Express mission[4]. However, the lack of a magnetic field around Mars means that this methane can be easily destroyed by cosmic radiation. Therefore, the fact that its abundance seems to remain more or less constant implies methane is being produced on Mars. But how?

Methane is usually associated with organic processes (as the output of processes involving life), but it can also be made by geochemical mechanisms, such as a process known as serpentinisation, or when released from meteorites bombarded with UV radiation (Mars-like conditions).

More data are needed to determine where Martian methane comes from, and sources are not mutually exclusive, so more than one may be at play.

2

2Titan Just as it has on Mars, methane has been detected in the atmosphere of Saturn's moon, Titan[5]. These observations have been confirmed both by Earth-based telescopes and the Cassini mission, which has also spotted shallow lakes of methane around the moons tropics. Calculations suggest that this methane ought to have been broken up by cosmic radiation within 50 million years or so (a very short time when compared to the age of the Solar System itself). Therefore, it's present abundance seems to indicate that the methane in the atmosphere is being replenished from a source on Titan itself – just like Mars. A likely source is cryovolcanoes (volcanic type features which release water and other gas/liquids with low melting points on colder worlds than our own). However, we can't assess whether there are any cryovolcanoes on Titan: the atmosphere is thicker than Earth's, and the layers are almost entirely opaque to visible light. As a result, we have no good images of the Titanian surface!

2

2Life in the universe – the Fermi Paradox

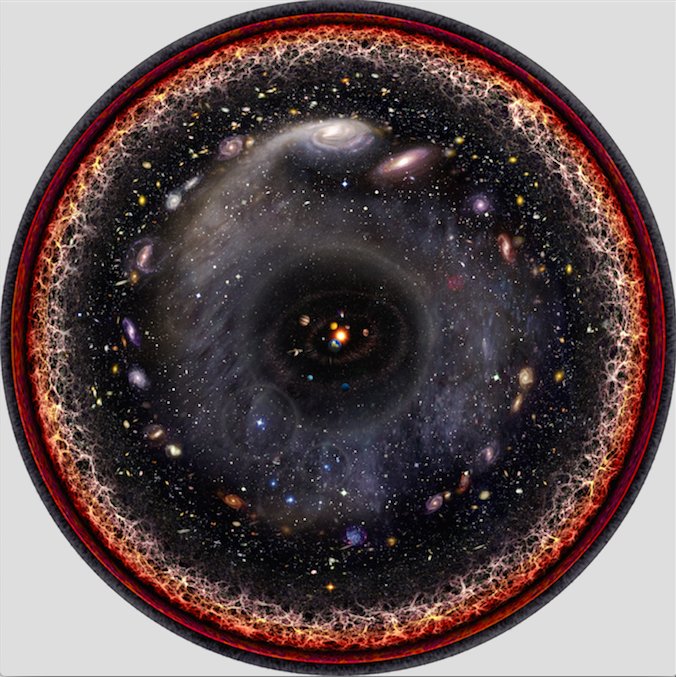

There are billions of stars older than our own sun, orbited by planets older than our Earth, so other Earth-like planets are likely in our observable universe: the universe that can, in principle, be viewed from Earth at this point in time. Anything further away won't have had time, due to the expansion of space (since the Big Bang), for its light to have reached us. The observable universe spans over 93 billion light years, giving us an estimate of at least 100 billion galaxies. These Earth-like exoplanets could've supported life for much longer than Earth, and host far more evolved civilizations!

The paradox is that, if these species are more technologically advanced than us, they may know we exist and have the space technology to reach us... so why hasn't it? One theory is that intelligent life arises frequently, but gets extinct before technology advances enough to make interstellar contact.

Learn more about Fermi paradox.

The origin of life

Despite the fact that we think life needs water, RNA is unstable in water unless the water has a high enough boron content. Boron stabilises ribose, the “R” in RNA. However, it's believed that when life began on Earth, there was hardly any boron in the water. So this leaves us asking, how did life begin?

One hypothesis, Panspermia, considers the possibility that life began outside our Earth. The most likely scenario for this hypothesis involves life originating on Mars. It is thought that boron was far more plentiful on Mars and this is supported by the fact that boron was found on a Martian meteorite[6]. While this may seem far fetched, the idea that basic Martian life could have travelled over on an asteroid and evolved on Earth at least answers the RNA water problem. So are we in fact the long lost descendants of Martians, or is there something we’re missing?

Learn more about Location of the Origin of Life.

3

3Maybe we are yet to come across alien life, because Earth is fundamentally unique. However, with probability in our favour, it’s likely we will stumble across alien life eventually. The next question will be, do we want to?

This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Andrew Rushby, Ed Trollope, Jon Cheyne, Cait Percy, Grace Mason-Jarrett, Rowena Fletcher-Wood, and Holly Godwin.

This article was first published on 2017-11-26 and was last updated on 2021-05-16.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Abbot, D, S., and Switzer, E,R., (2011). The Steppenwolf: A proposal for a habitable planet in interstellar space. The Astrophysical Journal, 735(2): L27. doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/735/2/L27.

[2] Leshin, LA et al. Volatile, Isotope, and Organic Analysis of Martian Fines with the Mars Curiosity Rover. Science 341.6153 (2013): 1238937. doi: 10.1126/science.1238937.

[3] Kawahara, H., et al., (2012). Can ground-based telescopes detect the oxygen 1.27 μm absorption feature as a biomarker in exoplanets? The Astrophysical Journal 758(1):13. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/758/1/13.

[4] Formisano, V., (2004). Detection of Methane in the Atmosphere of Mars Science 306(5702):1758-1761. doi: 10.1126/science.1101732.

[5] Clark, R,N., et al., (2010). Detection and mapping of hydrocarbon deposits on Titan. Journal of Geophysical Research 115(E10). doi: 10.1029/2009JE003369.

[6] Grossman, L., Webb, R., (2013). Martian chemistry was friendlier to life. New Scientist 219(2933):14. doi: 10.1016/S0262-4079(13)62173-9.

Recent extraterrestrial life News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles