Immune system

Article curated by Ginny Smith

Our immune systems are vital for our survival. They protect us from bacteria, viruses and other foreign pathogens that could cause us harm. But sometimes, they can go wrong. By better understanding how our immune system works, researchers hope to support and boost the system so it can fight invaders when necessary. More information will also help us discover how to correct it when it goes wrong, and treat allergies and autoimmune diseases.

![Sneeze James Gathany (CDC Public Health Image library ID 11162) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](/img/sci/1024px-sneeze.jpg)

One way that our body protects us from invaders is by forcibly expelling them – or, as we call it, sneezing. Sneezing occurs when something entering our noses irritates the lining and triggers an electrical signal. This signal travels to the brain stem, which initiates the sneeze response. While this much is understood, what scientists don't yet know is why some people tend to sneeze once, while others sneeze 2 or 3 times, and still others are plagued by bouts of many, many sneezes[1].

People who have many allergies are more likely to be multiple sneezers, particularly if they are exposed to their allergen over a long time period. It is also likely to be linked to differences in people's immune systems, and their brains, but what exactly these are, and why they cause people to sneeze differently, is yet to be discovered.

Allergies

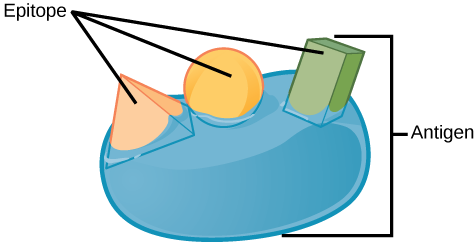

Allergies occur when the body treats something harmless, such as pollen, as a pathogen. The body mounts an immune response to the 'invader', to try and protect us from it – unfortunately, this causes the common allergic symptoms of runny nose and eyes, itching and rashes. In severe cases, the body can go into anaphylaxis, even leading to death if not treated.

Allergies are, at least in part, genetic – children born to parents with allergies are much more likely to suffer[3]. But this isn't enough to explain the rise we are currently seeing. One idea for the cause of this increase is known as the 'hygiene hypothesis.' This suggests that because we now keep our homes and children so clean, they don't come into contact with the number of pathogens our ancestors were used to, so their immune systems are never 'trained' in what to respond to. As a consequence, they are activated too easily in response to things that aren't harmful[4].

Another suggestion is that a change in diet is causing the increase. Other environmental factors, such as increases in pollution[5], have also been put forward, as has a link with the use of antibiotics. Determining which of these is true, or if there is another cause entirely, requires further research

Learn more about Rise in Allergies.

2

2

Autoimmune diseases

Another way in which the immune system can malfunction is in autoimmune diseases, where the body mistakenly reacts to its own tissues as if they were an invader that needs fighting off. These illnesses can affect the whole body (like in Lupus), or one specific part of it (e.g. Crohn’s disease attacks the gut lining). What causes people develop these diseases isn't known.

Genetic factors play a role, as relatives of those with an autoimmune disease are at higher risk of developing one, but environmental factors are also involved, and are thought to trigger the onset of the disease [6]. In some cases, autoimmune diseases may be triggered by infection, but some researchers think dietary factors or exposure to toxins in the environment can also be to blame. There are other factors, like sunlight, which seem to be protective. Understanding more about the causes of these illnesses may lead to improvements in their treatment, or even to measures which could prevent them.

3

3

One simple explanation could be that it is due to the differences in male and female immune systems – in many animals females have a more reactive immune system, which could put them at risk of autoimmune diseases. Human women do produce higher levels of antibodies than men, and show a stronger response to vaccinations, but what mediates this difference isn't known. Some studies have suggested oestrogen has an effect on the cells of the immune system, which could explain why women of childbearing age are most often affected. However, it could equally be that androgens, found in higher levels in men, offer some protection. Genetic differences between men and women could also play a role, or the ability of the organs to resist attack by the immune system[8]. However, research into other areas, such as brain injury, suggest females are better able to resist damage. Interestingly, the gender difference in MS is absent when looking at pre-pubescent patients, suggesting that something happens to girls at puberty to put them more at risk[7]. Whether this is a hormonal change or an environmental one is not clear. Pregnancy could also be linked to the gender difference – the immune system is suppressed by the developing foetus to prevent rejection, and this causes a cascade of changes to the mother’s immune system. Some types of autoimmune disease actually tend to improve during pregnancy, but in others it can trigger the onset of the illness. Finally, it could be a different in the levels of exposure to environmental influences, like infections or toxins, that makes women more susceptible, or a different response to exposure. All these theories need to be explored further if we are to fully understand these devastating diseases, and why they affect women more than men

Medical professionals are starting to believe the clitoris has a role in immune health. This is still in its early stages of studying, however, because the clitoris has a long history of being omitted from medical text books, and its three-dimensional structure was only first identified and depicted in 2009.

Encephalitis lethargic, or the sleepy sickness (distinct from sleeping sickness) is a disease of unknown origin. No virus nor bacteria has been linked with it, but the one epidemic that occurred between 1916 and 1926 did follow an epidemic of the Spanish flu. Similar bacteria found sporadically in modern sufferers suggests the flu bacteria may have triggered the immune system to attack the brain – an autoimmune reaction. If true, this would mean the damage is permanent.

2

2

![Hookworm larvae By Marina I. Papaiakovou (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](/img/sci/hookworm_larvae.jpg)

One interesting theory for the rise in both allergies and autoimmune diseases is linked to parasites[9]. Most animals in the world carry parasites – even parasites themselves! But in large portions of the world, finding a human with parasites is relatively rare. Removing parasites is seen to be a step towards improving human health, but it might also cause problems. Some people claim that our lack of internal passengers is to blame for the increase of allergic and autoimmune diseases, causing our immune systems to go into overdrive. Some trials have found that those with the highest parasite load show the lowest level of allergic reactions, while others have suggested infection may actually induce allergies and asthma.

Even if we do find a strong link between parasites and protection against these illnesses, why? Parasites are complex creatures – they may produce some chemicals, for example, that reduce the immune system’s response, but others that stimulate it. Researchers are trying to isolate key factors.

2

2Nodding syndrome, a compulsive nodding disease, is found in Western Equatoria State in South Sudan, northern Uganda, and Tanzania. This clustering should make it easy to diagnose, but the disease has tested negatively for inherited diseases, viruses, bacteria, heavy metal toxicity and nutritional deficiency. Theories focus on wartime chemical exposure, and the parasitic worm onchocerca volvulus, responsible for invading the eye and causing the disease known as river blindness. Whilst there is no evidence the worm invades the brain or causes seizures, this is a popular theory following blood tests showing previous exposure to the worm in sufferers – because the antibodies that kill it are in the blood. Scientists have suggested an autoimmune mechanism, where the antibodies designed to kill off the worms have started killing similar-looking brain cells. However, it’s also possible these proteins, normally found inside cells, may have spilled OUT when epilepsy destroyed them – making the antibodies cleaning them up a symptom not a cause. But these antibodies are not found in all sufferers. We also don’t know why the disease only affects children.

Could your own cells be used to treat autoimmune disease and organ transplant rejection? T cells, biological messengers that regulate the immune system and tell it when to and when not to turn on its defences, can be extracted, grown in petri dishes and then placed back in the body with the hopes of mediating immune response, for example, after genetic modification. This has the potential to deliver targeted immune acceptance or rejection, without turning the entire system on or off.

2

2Hangovers

As well as allergies and autoimmune diseases, there may be another effect of our immune system that causes suffering to a huge number of people – hangovers. Scientists don't fully understand hangovers – while it is known that consuming large amounts of alcohol causes dehydration, low blood sugar and changes in hormone levels the next day, why these should lead to the specific symptoms of a hangover isn't clear.

Now, some scientists are suggesting that it might be our immune system that is to blame. A study found that the day after a binge, the concentration of immune system messengers called cytokines found in the blood increases. If these same molecules are injected into healthy people, they cause hangover-like symptoms[10]. The theory is that our immune systems try to fight the alcohol in our blood stream, thinking it is an infection, and this is what causes the headaches, nausea and fatigue the following day. But alas it will be a while before we know whether this will lead to an effective treatment for hangovers!

Read more about what we don’t know about hangovers in our blog post.

2

2

In theory, cytokines stimulate a bigger immune response, but this pattern doesn’t always work out, suggesting there are still things we don’t know about cytokines. Cytokines are different from hormones, but scientists are still unsure how and why. Things they have noticed include that cytokines are produced by a wider variety of cells (pretty much anything with a nucleus), a particular cytokine may be produced by more than one kind of cell, and concentrations vary by more than a thousand-fold – highly unusual for hormones or classic proteins! Another mystery is the reach of cytokine effects; they can simply impact their parent cell, nearby cells, or the whole body – but what governs how far they can impact other cells is uncertain. As a possible therapeutic treatment against nerve injury or inflammatory pain, or an agent for vaccination, unweaving the unknowns of cytokines is an important medical challenge.

3

3Animal immune systems

Not all animals have identical immune systems, but one group of mammals has a mutation that makes it stand out from the others – the toothed whales. Recent research has discovered that these whales have a mutation in the Mx genes, which are responsible for producing virus fighting proteins, meaning they can't produce these proteins[11]. How they have survived without them is unclear, as the proteins are thought to be vital in fighting off illnesses like HIV and flu.

Baleen whales share a common ancestor with toothed whales, and they retain functional copies of the Mx genes, which suggests the toothed whales lost the gene after diverging from a common ancestor. This ancestor may have been exposed to a virus that forced the loss of Mx gene function in order to survive – a theory supported by the findings that some viruses today may exploit Mx gene function for individual gain. Whales must have evolved some sort of compensatory mechanisms to fight viruses, but we don't know what these are.

Learn more about Toothed Whales Survival.

3

3Vaccines

Vaccines work by giving our bodies a dose of a live, attenuated virus, or a deactivated one, so that it develops antibodies and learns how to kill off the virus next time it encounters it. Live viruses usually produce a stronger immune response, but vaccines can and do wear off. Recent discoveries suggest that the body has a long term and a short term memory in the immune system, so some immune responses can be strong, but short-lived, allowing the disease to be caught again and again. One example of this is cholera: catching cholera provides a long-lived immune response, the body remembers it and develops immunity, but scientists have not been able to replicate this with cholera vaccines, which provide only short-term immunity that wears off if you don’t keep having boosters. This can be dangerous where people miss boosters and assume they’re protected. Researchers are now using the new information about possible long and short term immune memory to develop vaccines that target the long term memory.

3

3The relatively untested chicken pox vaccine is one that might only provide short-term immunity. Tests have already shown the vaccines provide a lower chance of immunity than actually getting the disease, and may or may not protect against shingles – the reactivation of the hibernating virus many years later.

2

2

We don't know why singles happens, but one theory is that it's the result of age-related immune senescence. We also don’t really know what it is: the shingles blister contains the chicken pox virus and can cause chicken pox, but you can’t catch shingles from people with chicken pox.

3

3Another way to stimulate a stronger immune response could be through using chemical vaccines rather than biological ones, built from artificial carbohydrates. Research is ongoing, but if effective these vaccines could work without the need for immune response stimulating coatings.

2

2Sometimes vaccines are given therapeutically to already infected individuals with the hope of rousing their immune system to help them fight the disease off, such as injecting antibodies from an immune individual into an infected individual. Whilst this is often effective at fighting the disease, it might decrease the sufferer’s chance of producing antibodies themselves.

2

2Measles may act to suppress the immune system. After the measles vaccine was introduced in the 1960s, a rapid decrease in all infectious diseases was seen in vaccinated children. The effect measles has on the immune system has been dubbed "immune amnesia" – the ability to suppress and erase immunity.

2

2

Will we ever be able to vaccinate against cancer? Cancer cells being your own rather than foreign, this may seem impossible, but scientists are looking into ways to teach the immune system to recognise the difference between benign and harmful self-cells.

2

2What about diseases like HIV that actually destroy our immune system? This rapidly-mutating disease is a challenge for a healthy immune system to recognise, let alone one compromised by the effects of the disease. Currently, scientists are looking into therapeutic vaccination.

2

2Not all diseases need to mutate to deceive the immune system. Some have evolved decoy proteins that slow down the immune system (by hiding so the immune system doesn’t react in time), distract the immune system into attacking the wrong things (by squirting out decoy proteins in their wake that the immune system attacks preferentially) or disguise a pathogen as a harmless self cells by changing their protein surfaces to imitate cells round them.

3

3

3

3

Researchers are exploring the possibility of creating edible vaccines by genetically engineering plants we eat. This could potentially solve the logistic problems of multiple-dose vaccinations in developing countries. However, as we don’t normally exhibit immune responses against food, if we could provoke one, how would that impact the rest of our diet and our normal reactions to infectious agents? To read more about vaccines, take a look at our article on the topic.

3

3This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Ellen Moran, Ginny Smith, Johanna Blee, Rowena Fletcher-Wood, and Joshua Fleming.

This article was first published on 2016-03-03 and was last updated on 2019-06-28.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Erickson, M,H., (1940) The Appearance in Three Generations of an Atypical Pattern of the Sneezing Reflex The Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology 56(2):455-459 doi: 10.1080/08856559.1940.10534512

[2] Sense About Science (2015) Making Sense of Allergies http://senseaboutscience.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Making-Sense-of-Allergies-1.pdf

[3] Gough, H., et al., (2015) Allergic multimorbidity of asthma, rhinitis and eczema over 20 years in the German birth cohort MAS Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 26(5):431-437 doi: 10.1111/pai.12410

[4] Kramer, A., et al., (2013) Maintaining health by balancing microbial exposure and prevention of infection: the hygiene hypothesis versus the hypothesis of early immune challenge Journal of Hospital Infection 83:S29-S34 doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(13)60007-9

[5] Penard-Morand, C., et al., (2010) Long-term exposure to close-proximity air pollution and asthma and allergies in urban children European Respiratory Journal 36(1):33-40 doi: 10.1183/09031936.00116109

[6] Baumgart, D,C., Sandborn, W,J., (2012) Crohn's disease The Lancet 380(9853):1590-1605 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9

[7] Ngoa, S.T., Steyna, F.J. and McCombeb, P.A., (2014) Gender differences in autoimmune disease Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 3/ 35:347-369 doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.04.004

[8] Dai, C., et al., (2014) Genetics of systemic lupus erythematosus: immune responses and end organ resistance to damage Current Opinion in Immunology 31:87-96 doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.10.004

[9] Okada, H., et al., (2010) The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update Clinical & Experimental Immunology 160(1):1-9 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04139.x

[10] Kim, D., et al., (2003) Effects of alcohol hangover on cytokine production in healthy subjects Alcohol 31(3):167-170 doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2003.09.003

[11] Braun, B., et al., (2015) Mx1 and Mx2 key antiviral proteins are surprisingly lost in toothed whales Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112.26:8036-8040 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501844112

Blog posts about immune system

Recent immune system News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles